Mesa art history professor Dr. Denise Rogers hosted a presentation on Thursday Feb. 21 to provide historical context and background for the art of the Black Power movement, as part of Mesa’s celebration of Black History Month.

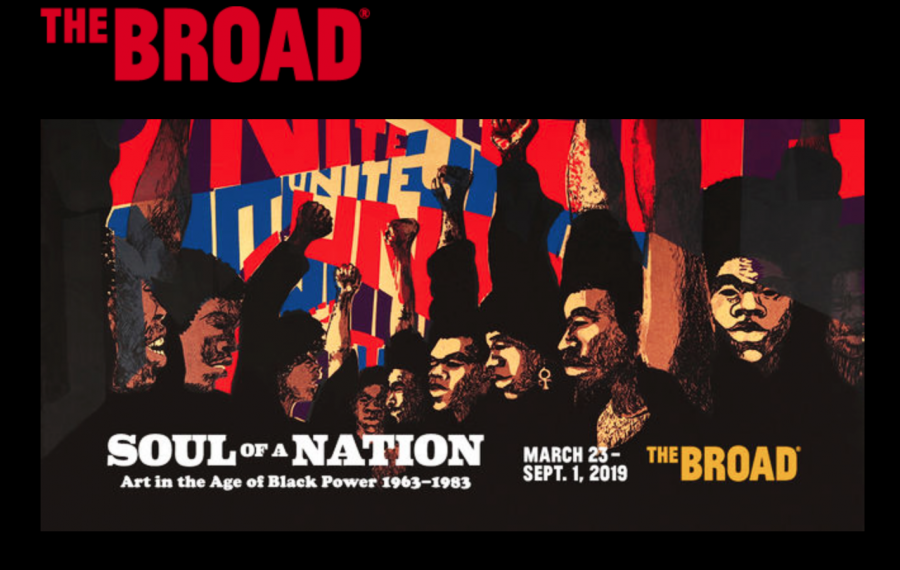

Rogers’ presentation functioned in part to highlight an upcoming contemporary art show, “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” arriving at The Broad in L.A. on March 23.

Some of the artists featured in “Soul of a Nation” made it into Rogers’ presentation, such as Faith Ringgold and Barkley L. Hendricks. But Rogers’ goal was not just to talk about Black-Power-era artists — it was to discuss the movements that inspired and ultimately enabled the Black Power art movement itself.

“I wanted to show that (the Black Power movement) didn’t just start,” Rogers said. “A lot of the artists who’re in the show were looking back at the artists of the early 20th century. They felt like they provided a foundation for them to not only be artists, but to look to Africa, and African forms and African ideas, and incorporate them into their work.”

The difference, she said, was that the Black Power artists transformed those things into expressions embodying their own perspectives.

Rogers put up a slide of pivotal figures who laid the philosophical groundwork of the Black Power movement, such as Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Dubois, Marcus Garvey, and Alain Locke. These people, Rogers indicated to the room, piloted the movement to shift society’s narrative of blackness away from hateful stereotypes.

A new slide confronted the audience: a collage of old propaganda illustrations rife with imagery left over from anti-black minstrelsy, such as an advertisement for the blackface minstrel show “A Darkley Misunderstanding,” as well as the film poster for D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation: The Fiery Cross of the Ku Klux Klan.” These images represented a slice of how American society characterized blackness at the start of the 20th century.

Rogers told the audience that big thinkers like Locke, who is often called the father of the Harlem Renaissance, believed it was necessary to recreate the image of black society. Locke wrote in his book, “The New Negro,” that for “generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more a formula than a human being — something to be argued about, condemned or defended … a social bogey or a social burden.”

But in overriding a racist visual narrative with expressions of the reality of black identities, he believed society would shift away from the mindset that beget and perpetuated black oppression. “By shedding the chrysalis of the old Negro problem,” Locke continues in the book, “we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.”

Rogers talked about Locke’s mission to gather together black artists attempting to recover their cultural history, as individuals whose ancestral lines were often unknown or obscured — obliterated by the reality of slavery.

Locke, she said, had noticed how European artists like Picasso and Matisse had begun to appropriate native African imagery and sculptures into their work, to the point that the art community associated African motifs as inherent aspects of European Modernism. One artist Rogers highlighted, Hale A. Woodruff, combatted that association in an attempt at reclaiming the imagery. His 1928 painting “The Card Players” was a Modernist take on a contemporary scene, but used African mask motifs to represent the players’ faces.

One of Rogers’ slides featured Palmer Hayden’s 1926 piece, “Fétiche et Fleurs,” translating to “Fetish and Flowers.” Rogers said that Hayden was an artist uncomfortable with the idea of reclaiming African imagery he was unfamiliar with. “Fétiche” was an underhanded jab at other artists and curators who did. The still life depicts a Fang reliquary sculpture atop a ceremonial cloth worn only by Kuba kings — two culturally unrelated and contextually sacred things placed like decorative baubles beside a vase of flowers.

Hayden’s and Woodruff’s approaches to reclaiming their histories were poignant studies in the dilemma black individuals face in defining their own cultural narratives.

Rogers related it to her own experience as a black woman. “It’s like reconnecting,” she explained. “You can’t miss it because it wasn’t something you ever experienced, but … learning about history gives you a sense of identity.” She added, “You’re getting a fuller perspective.”

Highlighting “Soul of a Nation” and the history behind the Black Power movement was important, Rogers thought, because it reflected today’s social climate.

“I think everyone feels a sense of anxiety and frustration,” she said, “wondering what direction we’re headed in.”

She continued, “Within this show, (the organizers are) focusing on this idea of unity, recognizing that there are things that are the soul of the nation that aren’t being addressed, that allow for certain actions or certain words to continue — and until we address those things, until we address the soul of the nation, nothing is going to change.”

According to The Broad’s website, “Soul of a Nation” will feature more than 60 influential artists from 1963 to 1983, exhibiting paintings, sculptures, photography, and more from the civil rights and Black Power movements.